The Characterization of Hysteria Throughout History

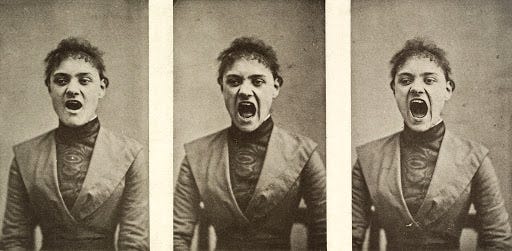

Throughout history, Hysteria was characterized as a “women’s disorder” and is “undoubtedly the first mental disorder attributable to women” (McVean). In fact, the label of Hysteria was simply utilized as “the medical explanation for ‘everything that men found mysterious or unmanageable in women’” (McVean). This bias and misogyny which was evidently at the root of Hysteria is further delineated as “many of the problems physicians were attempting to fix in female patients, were not problems when they presented in male patients” (McVean).

The characterization of Hysteria as a “women’s disorder” specifically led to a perception of Hysteria as linked to women’s sexuality. In fact, one reason women were barred admission to medical schools in the 1800s was men’s fear that “over-exercise of the brain would divert energy from the womb and lead to sterility and hysteria” (Porter, 357). Within this characterization of Hysteria emphasizing women’s femininity and sexuality, ideological nuances including religion and demonology were also prevalent. Throughout history and within various cultures, Hysteria was labeled a women’s disease and has been attributed to women’s femininity and sexuality as well as influenced by religion through demonological overtones.

In Ancient Greece and Egypt, Hysteria was characterized and rationalized by a link to women’s femininity and sexuality. Specifically, treatments and rationalizations for Hysteria revolved around the uterus. One particularly prominent theory in Ancient Greece and Egypt was that of the “wandering womb” or “roaming uteri”, which was bolstered by Plato and Aretaeus of Cappadocia’s work, noted in the Kahun Papyrus, yet disputed by Galen and Soranus of Ephesus. This theory posited that due to “an inadequate sexual life”, “poisonous stagnant humors”, and “toxic fumes” remain enclosed within the female body and thus the uterus is “restless and migratory” (Tasca et. al., 2012). As Ancient Grecians and Egyptians believed that the womb could affect the rest of the body’s health, they postulated that when the uterus migrates around the body, prominent pressure is placed on other organs and results in “any number of ill effects” (McVean). One of these ill-effects was believed to be Hysteria, and thus this phenomenon was also known as “hysterical suffocation” (McVean). The “wandering womb” theory delineates the gender bias at the core of Hysteria’s rationalizations through the theory’s emphasis on women’s sexuality and its supposed faults.

In viewing Hysteria from a linguistic lens, one may note a seed of this “wandering womb” theory and the perceived relationship between the uterus and Hysteria. Hippocrates, the first to use the term “Hysteria”, believed “that the cause of this disease lies in the movement of the uterus (‘hysteron’)” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Proposed treatments for this “wandering womb” theory included “placing good smells near the vagina, bad smells near the mouth, and sneezing” such that the “offending uterus was usually coaxed back into place” (McVean). Other treatments for Hysteria centered around marriage and the maintenance of an “adequate sexual life”. The treatment of marriage was proposed by numerous doctors for female psychological disorders (Porter, 82) and Hippocrates suggested that “even widows and unmarried women should get married and live a satisfactory sexual life within the bounds of marriage” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Even Plato argued that “the idea of a female madness related to the lack of a normal sexual life” in Timaeus (Tasca et. al., 2012). Furthermore, marriage was promoted as a treatment for Hysteria as “the retention of menstrual blood” was also believed to cause Hysteria and the “implied regular sexual intercourse” of marriage would induce the purging of this blood (McVean). Thus, it is evident that Hysteria’s diagnosis was a means of exerting male influence over increasingly intimate aspects and choices in women’s lives.

Conversely, Soranus posited that women’s disorders are caused by “the toils of procreation” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Thus, in order for women to recover they must abstain from sexual activity (Tasca et. al., 2012). Galen presented yet another theory: “The retention of ‘female seed’ within the womb was to blame for the anxiety, insomnia, depression, irritability, fainting and other symptoms women experienced” (McVean). Thus, in Ancient Greece and Egypt the blossoming theories and treatments for Hysteria consistently sought to control women’s femininity and sexuality. This theme is consistent as in the Renaissance the uterus is still utilized “to explain [the] vulnerable physiology and psychology of women” (Tasca et. al., 2012).

During the Modern Age, Hysteria’s characterization and rationalization was influenced by women’s femininity and sexuality. One specific theory postulated during the mid-19th century by the American physician Silas Weir Mitchell cited women’s inability to tolerate “overstimulation of the mind” as Hysteria’s cause (Jaffray). Therefore, Mitchell’s prescribed cure was the “rest cure”, in which women were “confined to bed, force-fed rich, fatty foods, massaged, and electro-shocked (in some cases)” (Jaffray). The “rest cure” was infamously delineated through “The Yellow Wallpaper”, a semi-autobiographical short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman which discusses the psychological anguish induced by the cure prescribed by Mitchell for Gilman’s postpartum depression (Coffey). However, in addition to Mitchell’s “rest cure”, the theory of the “wandering womb” remained present and led to an alternate Victorian Age treatment: smelling salts (Tasca et. al., 2012). It was believed that women “were inclined to swoon when their emotions were aroused” and, as dictated by Hippocrates, the “wandering womb” is repelled by the “pungent odor” of smelling salts (Tasca et. al., 2012). Therefore, by women carrying “a bottle of smelling salts in their handbag”, the “wandering womb” would return to its proper location and women would “recover her [their] consciousness” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Thus, it is evident that rationalizations and treatments for Hysteria during the Modern Age continued emphasizing women’s femininity and sexuality as men attempted to exert authority over women and justify male superiority.

From the Middle Ages through the Contemporary Era, Hysteria’s characterization and rationalization was influenced by a demonological perspective yet remained linked to women’s femininity. More specifically, mental illness and demonology’s intertwining was often linked to women through witchcraft as well as women’s supposed manipulation. In the Middle Ages, the relationship which developed between mental illness and demonology is evident as Hildegard of Bingen, a German abbess and doctor, states that “melancholy is a defect of the soul originated from Evil” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Furthermore, mental illness was believed to serve as an “obscene bond” between women and the Devil; because Hysteria was “confused with sorcery”, women who were believed to be “Hysterical” were subjected to exorcism (Tasca et. al., 2012). In the Renaissance, this intersection of witchcraft — which was attributed primarily to women — and mental illness continued as Hysteria was the diagnosis explaining “the so-called manifestations of bewitchment” (Porter, 243). In a slight departure from the demonological viewpoint on mental illness of the Middle Ages, Dutch physician Johann Weyer believed that “witches were mentally ill and had to be treated by physicians rather than interrogated by ecclesiastics” (Tasca et. al., 2012). As such, this ideology begins to adopt a more rational and less demonological perspective on Hysteria as it identifies “witches” as individuals who are simply mentally ill and promotes medical treatment in response. Marion Starkey, an American history book author, presents an alternate viewpoint during the Modern Age which highlights the negative influence of religion upon mental illness. Starkey believed that Hysteria manifests in “young women repressed by Puritanism, and was aggravated by the intervention of Puritan pastors” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Though the departure from prescribed religion through demonology and witchcraft was previously considered at the root of mental illness, here Starkey posits that the oppression of religion is in fact the cause of Hysteria. During the Contemporary Age, women remained linked to demonology and were viewed as manipulative and uncontrollable. More specifically, women were viewed as “unaware of evil forces”, “‘out of control’ from reasonableness”, and demonstrating “manipulative behavior that seeks to achieve an improper position of power” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of “secondary advantage” further demonstrates this ideology as he posited that “woman has no power but ‘handling’, trying to use the other in subtle ways to achieve hidden objectives” (Tasca et. al., 2012). As such, the Contemporary Age presents a slightly modern take on the demonological perspective on Hysteria as the manipulation which Freud states that women seek to achieve is in a similar vein to witches’ portrayal as utilizing dark forces to achieve direful means. Thus, from the Middle Ages through the Contemporary Age, there was a widespread belief in the relationship between women, mental illness, and demonology which was evident through Hysteria’s characterization and rationalization. Through labels of handling and witchcraft, this relationship primarily served to emphasize the narrative of women’s supposed association with demonology and evil as well as that any power that women may gain will only be used to manipulative and direful ends.

Hysteria was influenced by religion, demonology, and women’s sexuality throughout history while maintaining its depiction as a women’s disorder. However, despite this depiction of Hysteria as a women’s disorder, Jean Martin Charcot — who characterized Hysteria as a neurological disorder — demonstrated that the “disease is in fact more common amongst men than women” (Tasca et. al., 2012). Though “men were as prone to nervous breakdown as women were”, Hysteria was not diagnosed in men as this would have “called into question the difference between the sexes” and shattered the patriarchy’s foundation (Tucker). Therefore, it is evident that Hysteria’s consistent characterization as a women’s disorder was not due to bolstered empirical evidence, but simply a symptom of bias against women, a view of women as inferior, and general misogyny. Though Hysteria is no longer deemed a women’s disorder nor is it a label for any mental disorders, the double standard for men’s and women’s traits and behavior remains prevalent. For example, while leadership in men is lauded, women’s leadership labels them as “bossy”. Furthermore, variations upon Hysteria such as “hysterical” remain utilized in our current language to describe supposedly overly emotional women. For example, women that cry in the workplace are often deemed hysterical. Therefore, though we have discarded the characterization and label of Hysteria as a mental disorder, specifically one which solely occurs in women, we must review the labels used for women’s behavior in order to reduce bias, a double standard, false labels, and misogyny.

Sources:

- Jaffray, Sarah. “What Is Hysteria?” Wellcome Collection, 13 Aug. 2015, wellcomecollection.org/articles/W89GZBIAAN4yz1hQ.

- Coffey, Rebecca. “Living with Hysteria: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and ‘The Yellow Wall-Paper.’” OUPblog, 20 July 2018, blog.oup.com/2018/07/hysteria-charlotte-perkins-gilman-yellow-wall-paper/#:%7E:text=After%20three%20months%20of%20marriage,He%20offered%20two%20cures.

- Tasca, Cecilia, et al. “Women And Hysteria In The History Of Mental Health.” Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, vol. 8, no. 1, 2012, pp. 110–119., doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110.

- McVean, Ada. “The History of Hysteria.” Office for Science and Society, 31 July 2017, www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/history-quackery/history-hysteria.

- Tucker, Abigail. “History of the Hysterical Man.” Smithsonian Magazine, 5 Jan. 2009, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/history-of-the-hysterical-man-43321905.

- Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (The Norton History of Science). 1st ed., W. W. Norton & Company, 1999.